Learn more about professional learning opportunities below, plus Tier 2 and Tier 3 strategies and interventions that can be explored by watching an introductory video to the strategy or intervention (where available) and downloading supporting documents.

2025-2026 Ci3T Project EMPOWER

These 2-hour stand-alone sessions on Zoom are free — come to one, come to all! See flyer for details, dates and times, and registration link, or register here.

2025-2026 EMPOWER

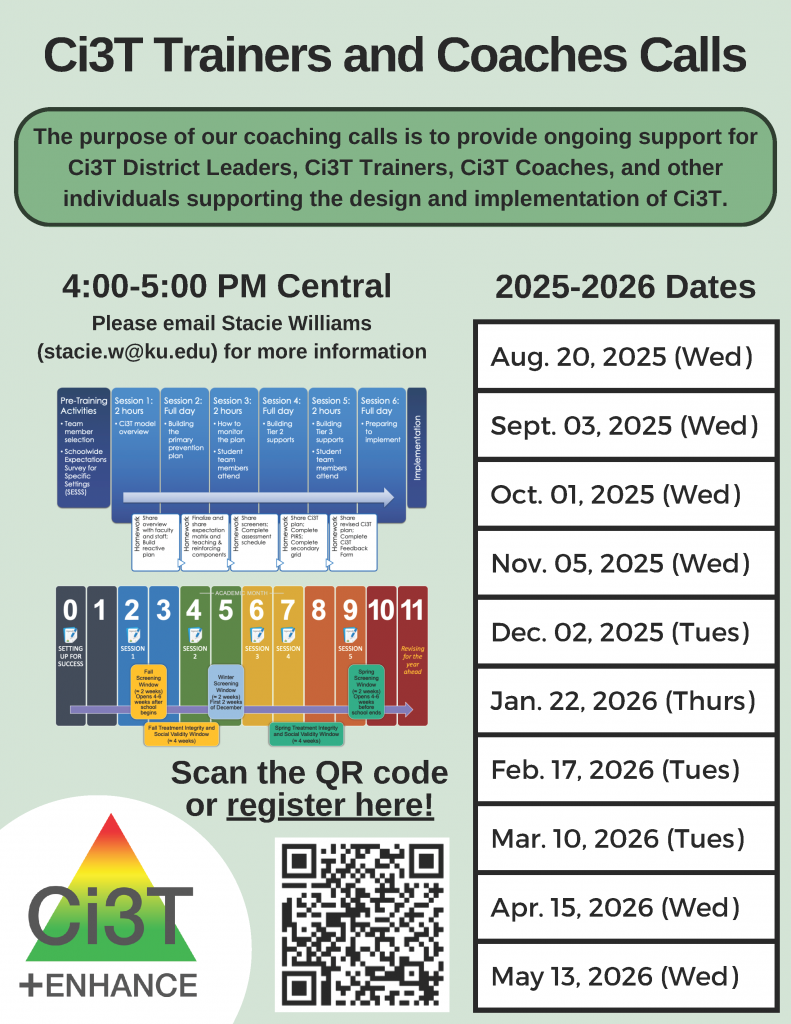

2025-2026 Ci3T Trainers and Coaches Calls

The purpose of our coaching calls is to provide ongoing support for Ci3T District Leaders, Ci3T Trainers, Ci3T Coaches, and other individuals supporting the design and implementation of Ci3T. We offer these calls as a service activity to support those committed to meeting students’ multiple needs in academic, behavior, and social domains. Open to all interested parties — to join these calls, please register here!

TIERED INTERVENTION LIBRARY

Learn more about Tier 2 and Tier 3 strategies and interventions below by watching an introductory video and downloading supporting documents. In these materials you will learn more about each strategy, why it is effective, the research supporting its use, and how to evaluate treatment integrity and social validity. Also included are PDFs and/ or Microsoft Word documents of what the intervention would look like as described in a school’s tiered intervention grid, research article references, practitioner article references, and more.

Professional Learning

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab. REPEATED READINGS (POSTED DECEMBER 28, 2015)

- Introduction

- PowerPoint presentation

- Sample peer checklist

- Sample student data collection graph

- Sample teacher data collection form and graph

- Intervention grid: PDF or MS-Word

- Implementation checklist

- Treatment integrity checklist

- Social validity: student forms

- Social validity: student forms scoring overview PowerPoint.pptx

- Social validity: student forms scoring guide

- Social validity: student forms scoring tool.xlsx

- Social validity: adult forms

- Resource guide

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.  Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab.

Good news! These materials have been enhanced and can now be found on the Enhancing Ci3T Modules tab. Project EMPOWER from the Past

2024-2025 EMPOWER

2024-2025 Project EMPOWER+ S7 Agenda (Ci3T Research Team led)

2024-2025 Project EMPOWER+ S7 Agenda

2024-2025 Project EMPOWER+ S7 Presentation

2024-2025 Project EMPOWER+ S7 Pacing Guide

2024-2025 Project EMPOWER+ S7 Video Recording

Handouts

Handout 1: Function Matrix Practice

Handout 2: Measurement Practice

Handout 3: A-R-E Component Practice

2023-2024 EMPOWER

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S1 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S1 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S1 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 1

Project ENHANCE Version (featuring modules)

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S1 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S1 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S1 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 1

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S2 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S2 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S2 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 2

Project ENHANCE Version (featuring modules)

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S2 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S2 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S2 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 2

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S3 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S3 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S3 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 3

Project ENHANCE Version (featuring modules)

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S3 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S3 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S3 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 3

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S4 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S4 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S4 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 4

Project ENHANCE Version (featuring modules)

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S4 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S4 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S4 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 4

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S5 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S5 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S5 Pacing Guide

Managing Acting-Out Behavior Resource Guide (video links included!)

Video recording Session 5

Project ENHANCE Version (featuring modules)

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S5 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S5 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S5 Pacing Guide

Managing Acting-Out Behavior Resource Guide (with video links!)

Video recording Session 5

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S6 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S6 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER T-Ci3T S6 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 6

Project ENHANCE Version (featuring modules)

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S6 Agenda

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S6 Presentation

2023-2024 EMPOWER E-Ci3T S6 Pacing Guide

Video recording Session 6

2022-2023 EMPOWER Zoom

2021-2022 EMPOWER Resources

2021-2022 EMPOWER S2 Presentation

2021-2022 EMPOWER S2 Notes

2021-2022 EMPOWER S2 Pacing Guide

Function-Based Reinforcer Menu

Setting Expectations Lesson Plan Exemplar

Setting Expectations Lesson Plan Template

Ci3T Integrated Lesson Plan Template

Video recording Session 2

2020-2021 EMPOWER Resources

2020-2021 EMPOWER S4 Presentation

2020-2021 EMPOWER S4 Notes

2020-2021 EMPOWER S4 Pacing Guide

Video recording not available

2020-2021 EMPOWER S5 Presentation

2020-2021 EMPOWER S5 Notes

2020-2021 EMPOWER S5 Pacing Guide

Video Recording Session 5:

Overview of Ci3T

Internalizing behaviors

Anxiety strategies

Relaxation training

Relaxation protocol

Self-monitoring

Cognitive restructuring

Functional assessment-based interventions

Anxiety strategies to share with parents